Recently, I had the wonderful opportunity to conduct this interview with Karolina Watroba, a scholar of German literature and culture. Watroba’s work challenges traditions of academic analysis and promotes stronger and deeper connections between the scholarly community and a broader reading public. Watroba’s recent work on Kafka, seen below, rests beautifully on the boundary between creative nonfiction, memoir, and academic scholarship. The book, Metamorphoses, traces Kafka’s legacy, impact, and influence from his times to the present, and from his center in Prague to a global community of readers. Those immersed in the Kafka world will find fresh insights and perspectives in these pages. Those new to Kafka will discover a generous and smart introduction to his world—and ours.

I’d like to thank Karolina Watroba for the time she took and effort she gave to provide rich responses to the interview questions.

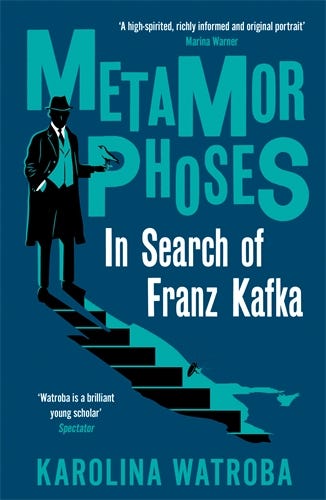

Dr Karolina Watroba is a scholar of German and Comparative Literature based at the University of Oxford and the Swedish Collegium for Advanced Study. She is the author of Mann’s Magic Mountain: World Literature and Closer Reading (Oxford University Press, 2022), which was shortlisted for the Waterloo Centre for German Studies Book Prize, and Metamorphoses: In Search of Franz Kafka (Profile, 2024), which was named an Economist Book of the Year.

SR: I’d like to start by asking about a favorite Kafka piece of yours. What would you pick? What draws you to it?

KW: Right now I feel like picking Der Verschollene (known in English as The Man who Disappeared or America), probably because I’m about to visit New York for the first time. When I first read it, I was surprised to learn that Kafka’s early novelistic imagination was like this – drawn to the picaresque, the (to him) exotic, but also to the position of the working masses within the technocratic order. It was different from the commonplace image of Kafka I’d had initially, as a brooding loner lost in the labyrinthine streets of Prague. I particularly enjoyed Kafka’s take on the exhausting mechanics of work at a big hotel, from the way that the elevator needed to be operated to the emotional and social demands of working at such close quarters with others. It was both a lesson in how varied Kafka’s writings are, and in how connected to the literary hive mind he could be: Central European literature of that period is full of compelling microcosmic hotel settings.

SR: Did you have an early, impactful experience reading Kafka? Can you describe this moment?

KW: I think Die Verwandlung (The Metamorphosis) was the first piece of literature I ever attempted to read in German. I was in high school and had been learning German for about five years; in Poland, where I grew up, most schoolchildren learned English and German. I always loved the idea of learning languages but had initially been a reluctant student of German, not least because of its prevailing associations at the time – the language of the former aggressor, occupier, and now (this was around 2000) of an economic powerhouse next door, where hundreds of thousands of Poles were emigrating to find work. Most of our teaching at school was very functional and unlovely: topics like recycling, illnesses and injuries, sports and exercise. Before I learned more about Kafka, about Prague, about his Jewishness, any of the historical or cultural context, it was thrilling just to interact with the language, for the first time liberated from the utilitarian shackles of textbook German. I don’t actually remember very much from that first reading, other than learning a lot of new words. It pleases me now to know that there are some common, everyday German words that I was for the first time exposed to through Kafka’s writing, that it will forever be the first context in which I encountered them. That’s a privilege that native speakers of German don’t have!

SR: Metamorphoses: In Search of Franz Kafka is perched at the border between academic scholarship and works that target a general audience. How did you decide on this method? What do you think this way of working with Kafka can achieve that more traditional academic work or more traditional narrative nonfiction cannot?

KW: My first book was about non-academic readers of Thomas Mann’s The Magic Mountain: it’s an academic monograph, based on my doctoral work, in which I show that Mann’s novel has developed something of a cult following in the century since its publication, in many different communities, ranging from tubercular patients to German prisoners of war, and including many acclaimed international writers and filmmakers. This had not been really acknowledged or engaged with in academic scholarship before, which tended to present The Magic Mountain as a towering intellectual achievement that is best – or only – read within the confines of the university. Embarking on my second book project, I thought that Kafka would be an interesting counterpoint to Mann because his endless popularity with readers is so obvious, and yet it still seemed to me that many academics often approached non-academic readings of Kafka as more of a necessary evil, an embarrassment that had to be diplomatically tolerated, rather than a trove of interesting information about why and how people come to care about his writing. This made me think a lot about the relationship between academic scholarship and readers outside of academia, or the lack thereof. I wanted to write a book that would be accessible to readers outside of academia – in terms of style, background information, and so on, but also accessibly priced and widely available in bookshops – while applying the same level of rigour, expertise, and intellectual curiosity that I bring to my academic writing.

SR: To follow up on the previous question, Metamorphoses emphasizes or asserts the subject position of the narrator, and in this way reads somewhat like a memoir of your journey to trace Kafka’s status and legacy across various physical and cultural spaces. That being said, the first-person narrative voice is developed only to a certain extent, meaning that the book, after all, doesn’t function as a memoir. Can you discuss the process of positioning your narrative voice in the book, deciding how much of your personal story to include and what to exclude?

KW: I’d say I was already bringing a lot more of this first-person perspective into my academic writing, which tends to delight some colleagues and doubtlessly puts off others. When I first started studying German at Oxford, I wanted my background – that I was one of many Eastern European immigrants in the UK, that I didn’t have any prior connection to England, that I learnt German for very different reasons to other students there, that I didn’t understand or fit into the British class system, and so on – to be irrelevant. I still cherish all the opportunities I got back then and still get every day to exist as a student and now scholar evaluated primarily on the basis of my expertise, skills, and academic achievements, irrespective of where I was born, how I grew up, what language I speak at home, and so on. But with time, and especially after Brexit, I also grew more critical of how I had come to be so reluctant to be identified with my background – it involved a lot of internalized xenophobia, no doubt. Once I was more comfortable accepting that, I was also able to see more clearly how the non-academic forces that shaped my life also continue to influence me as a reader and scholar, just as they influence other readers and scholars, whether they are conscious of this or not. In my research and writing, I aim to bring these forces to light, and that’s why I often adopt a first-person narrative voice, even if I’m not writing a memoir.

SR: Your chapters are organized by location–Oxford, Berlin, Prague, etc. Toward the end of the book, you have a fascinating and beautiful chapter titled “Seoul” about contemporary South Korean engagement with Kafka. What brought you to this particular literary context?

KW: I’ve been interested in the literary culture of South Korea for a long time, and I’ve been learning Korean since 2017. Initially this was just a parallel interest, nothing to do with the Kafka project. But as it so often happens – that’s one of the reasons why I find it so intellectually stimulating to be a comparatist, reading widely across various languages – I started noticing explicit references to Kafka in lots of Korean books I was reading. I thought it probably wasn’t just down to the Baader-Meinhof phenomenon and so started researching! Several Korean Germanists have published studies of the widespread reception of Kafka in Korea – among scholars, translators, and literati, as well as in popular culture – mostly in Korean, with a couple of summaries also available in German (and soon a new journal article in English by my colleague Dr Haneul Lee). I was excited to introduce this context to more readers in English and connect it to the realities of the book market and the position of translated literature in the English-speaking world, including the comparisons to Kafka which accompanied the success of Han Kang’s The Vegetarian in translation.

SR: When I first read Han Kang’s The Vegetarian, I also thought immediately of Kafka, though the styles of the two writers are quite different. How would you characterize the similarities and differences in the works of these two writers?

KW: My primary argument about The Vegetarian in the book is that the comparisons to Kafka were used early on, when Han Kang was being first introduced to English readers – on the cover blurb, by the Booker judges, and in press coverage – to carve out a space for her on the book market and lend her writing a certain prestigious European modernist pedigree. I also wanted to show that this was far from an isolated case, but more of a trend in how international literature, especially from East Asia, is often marketed to Western readers. But it is not just a vacuous marketing trick: Han Kang, and many other writers compared to Kafka who I discuss in the book, are in fact very familiar with Kafka and cite him as one of the formative influences on their work. His writings have been present in those literary cultures for decades, through translation, scholarship, and intertextual allusions and borrowings by dozens of writers, many of whom have never been translated into English. Interestingly, in Korea this has been particularly the case with women writers. Kafka’s powerful, memorable, visceral images of confinement, restriction, withdrawal, and impassioned yet enigmatic self-denial, familiar from stories such as The Metamorphosis and The Hunger Artist, have resonated with many readers around the world, among them Han Kang and several other Korean women writers of note. But it would be reductive to try and explain The Vegetarian solely or even primarily through the lens of Kafka, since it flattens so many other literary influences and her own distinctive sensibility.

SR: What are some of the most important things you learned from your “search” for Franz Kafka in contemporary culture? And how have your own perspective(s) on Kafka changed as a result of the encounters you had researching and writing the book?

KW: Sometimes in literary scholarship what is produced under the heading of ‘reception’ amounts to a list of influences and allusions, or an attempt to categorise, to create a neat systematic account that can be summarised in a couple of sentences as a postscript to literary analysis. What I try to do is show the texture of encounters that readers have with literature, to give it more space, and allow it to be its own story, meaningful in its own right. One important thing I’ve learnt in the process is just how much various readers, and communities of readers, tend to see their attachment to Kafka as unique, deeply personal, and utterly idiosyncratic – in ways that are actually very comparable across language, time, and space, for example looking at how Kafka was read by dissidents during the dictatorships in Czechoslovakia and South Korea. But this is very much not to say that all these individual readers are somehow deluded: their experiences are both comparable, and particular. I believe that good cultural criticism is able to both capture universal similarities and bring out the specifics of different situations, and that’s what I tried to do in the book. And all this naturally applies to me as a reader too – encountering other readers and their attachments to Kafka helps me see my own perspective as both particular and generalisable, and I hope that it makes me a better, more generous scholar, teacher – and book club member!

SR: I’d like to turn for a moment to academia. While there are references to a few academic texts in Metamorphoses, most of the works you discuss are not academic. There is not a single reference in the book to the realm of literary theory that has dominated the academic discussion of literature, including Kafka’s work, for decades. Can you discuss this choice? Do you think the academic study of literature is breaking up with theory? What do you see as the future of academic literary criticism? Do academic literary critics need to produce work, like yours, that’s more accessible and relevant to non-academic audiences?

KW: There were two reasons behind this choice. First of all, in my analysis I was largely following the interests, fascinations, and obsessions of Kafka’s readers outside of academia – and these have often involved a fascination with Kafka’s life and cultural context, among other things, but rarely involved highly theoretical approaches to his works, doubtlessly at least in part because such ways of reading often remain the preserve of the narrow cultural elite of the initiated. There are of course interesting stories to tell about such readers; in the book, I mention John T. Hamilton’s recent study, which is very good, in which he essentially rewrites the history of French theory, from Sartre and Beauvoir to Barthes and Derrida and beyond, as a series of readings of Kafka. But I didn’t foreground such theory-driven readers and readings in my book because – and that’s my second reason – they already dominate so much of what it written about Kafka. I didn’t feel that we necessarily need another book about Kafka and literary theory, at least not one written by me. But I did feel the need to learn, think and write about Kafka as read by and meaningful to those who are not literary theorists, and much of my work more generally is animated by this persistent gap between how and why scholars talk about books and how and why other readers talk about them. I hope that bridging this gap can be good and interesting for both groups, not least because all scholars are also readers, and – as I have learnt by doing this work – non-academic readers actually have a tremendous appetite for interacting with academic scholarship when it’s made accessible.

SR: You have worked extensively on the works of the German writer Thomas Mann, and especially on his novel The Magic Mountain. 2024 was the centenary of both Kafka’s death and the publication of The Magic Mountain. How would you compare the position of Kafka and Mann in today’s culture?

KW: Well, Kafka certainly “won” – in the sense that he is much better known, more widely read, more iconic. But luckily literary tradition is not a zero-sum game, and Mann is still widely read too, and functions as an important point of reference for many contemporary writers, although often more as an irritant rather than patron saint, as tends to be the case with Kafka. Just a few months ago English readers had a chance to encounter a great example of the former: The Empusion by my compatriot Olga Tokarczuk, a very overt rewriting of The Magic Mountain from a feminist and postimperial vantage point. I have recently written in the Times Literary Supplement about how Mann and Kafka have long been read against each other – notably in György Lukács’s essay ‘Franz Kafka or Thomas Mann?’ – but had not in fact seen each other as adversaries themselves. This was partly because in their lifetimes, their careers reached such different stages: by the time Kafka died in 1924, most of his writings had not yet been published, whereas with the publication of The Magic Mountain that year, Mann established himself as the most prominent German writer alive. But the difference in status was not the only reason; they also admired each other’s writings, as we know from their letters and diaries.

SR: What is next for you? What are you currently working on?

KW: In my next book – the title I have in mind is Weimar Worlds: A New Cultural History of Interwar Germany – I set out to illuminate the hidden cultural diversity of Weimar Germany. This epoch has often been characterized as a period of unprecedented cultural flowering, interrupted in 1933 by the formation of the Nazi government, but subsequently exported around the world by numerous illustrious exiles: Bertolt Brecht, Thomas Mann, Fritz Lang, George Grosz, Walter Gropius, and so on. I want to revise this narrative by showing that Weimar culture was not only exported, but also imported. In the 1920s and 1930s Germans were assimilating international cultural influences, but this process has not yet been sufficiently understood, especially where it involved influences from outside of Europe and USA. Yet Weimar Germany was a refuge for exiles and a destination for expats from all around the world, especially Asia. These newcomers to Germany co-created Weimar culture, which I want to show by looking at texts, authors, and institutions that were widely known and critically acclaimed in the 1920s and 1930s but have since been largely forgotten: relegated to specialist publications and not included in mainstream academic or popular accounts of the Weimar years.

Well done Seth. What a gem this author is. Profound insights