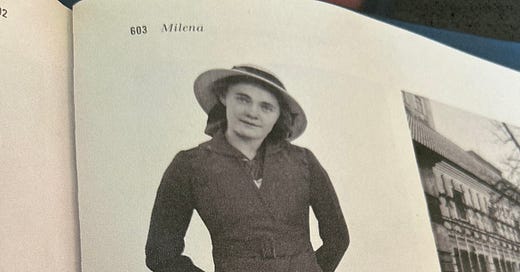

“Is this Milena?” The graphic artist working with us on redesigning FRANZ texted me a photo snapped from my copy of Hartmut Binder’s Kafkas Welt (Kafka’s World), an extraordinarily comprehensive pictorial account of the writer’s life. The chapter heading, Milena, appeared in the upper left-hand corner of the page with a photograph of a woman, but no caption was visible. I replied, “It must be, but I’ll confirm when I’m back in my office.” When I checked, however, the caption revealed that the woman was not Milena Pollak, née Jesenská (1896-1944), the 24-year-old Czech journalist and translator with whom Kafka had an intense epistolary relationship in 1920. Instead, it was Milena’s friend Jarmila Reinerová, née Ambrožová (1896–1990).

The resemblance had not gone unremarked on during Kafka’s correspondence with Milena, as is evident in his letter dated August 17–18, 1920: “I recognized J[armila] immediately, although she scarcely resembles the photograph, and doesn’t look like you at all; perhaps the only thing she does resemble is death.” Kafka’s description only grows more scathing as it continues: “The face pale (not exactly gaunt), the teeth half gold half cracked and rotted, the eyes as expressionless as on an eyeless statue,” and so on. Yet this portion, beginning with the comparison to death, is missing from the sole existing English translation of Kafka’s Letters to Milena, a reflection of the complex editorial history behind the text.

The correspondence began when Milena asked Kafka for permission to translate his story “The Stoker” into Czech. She and her husband, the German-speaking Jewish writer Ernst Pollak, moved in the same Prague literary circles as Kafka. By then, the Pollaks were living in Vienna, where Ernst’s infidelities strained their marriage. As Kafka, then 37, became increasingly invested in this passionate and fraught exchange, his characteristic inner conflict deepened.

A collection of Kafka’s letters to Milena was first published in 1952 by Willy Haas, a friend of both correspondents. Milena had entrusted the letters to Haas in 1939, before her death in 1944 at Ravensbrück concentration camp. In his afterword, Haas explained that he had cut certain passages that could be damaging to people still living, including himself, and alluded to “a certain tragic incident” that Kafka had purportedly misrepresented. The nature of the deleted material became clear with the publication of a 1986 German edition by Michael Müller and Jürgen Born, which reinstated all but four passages. Prominent among the restored sections were Kafka’s comments on Haas’s affair with Jarmila, whose husband, Josef Reiner, had died by suicide—an outcome Kafka attributed to the affair. Haas later married Jarmila, who was alive at the time of both the 1952 and 1986 editions.

In 1990, Schocken Books published Philip Boehm’s English translation of Letters to Milena, based on the Born-Müller edition. As Boehm noted in his introduction, the translation retained the four remaining omissions, whose “publication would be unlawful as well as indiscreet.” These four passages, we now know, concerned Jarmila, who died that same year at the age of 94.

In 2013, when the fourth volume of the German critical edition of Kafka’s complete letters, covering 1918–1920, appeared, these previously withheld passages finally came to light. Until now, however, they have not been translated into English. Below, I present them. These excerpts would fill in the gaps marked by [...] in the Schocken edition of Letters to Milena. They reveal Kafka’s mercilessness toward Jarmila and her role in a situation that ended in tragedy while, in many ways, mirroring his own love triangle with Milena and Ernst Pollak. Thus, they deepen our understanding of the complex emotional dynamics underlying his correspondence with Milena.

July 27, 1920

Jarmila. You’re probably right. Even what she says about M. [Josef Mareš], who “should be shot,” is insane. He’s supposed to be shot because he watched R. [Reiner] dying for one evening, and she’s allowed to pronounce judgment and herself watched him dying for weeks on end. But this much I know: I have no right to judge Jarmila, I don’t dare say anything more, and what I said, I retract.

August 17–18, 1920

…perhaps the only thing she does resemble is death. The face pale (not exactly gaunt), the teeth half gold half cracked and rotted, the eyes as expressionless as on an eyeless statue and, since it’s impossible to be so expressionless, once again very expressive, eyelids slightly inflamed (she must have been weeping), the cheekbones strong (now it’s Russian, now whorelike, now criminal, the sense eludes one).

August 17–18, 1920

How can someone who’s killed someone be so dead herself? And when has a man killed himself because of a woman and not, rather, for his own sake? Did she write the command: “Now poison yourself!” into her eyes or was it, almost without her knowing, inscribed there? That it was there is certain, so exhausted, so empty are her eyes from it.

September 7, 1920

I have never known a person who belonged so little to herself as Jarmila and yet was not insane.

English Translation Copyright © 2025 Ross Benjamin

All translations based on Franz Kafka: Briefe. Kommentierte Ausgabe. Herausgegeben von Hans-Gerd Koch © S. Fischer Verlag GmbH, Frankfurt am Main 1999.

Light and shadow.