Translated from the German by Ross Benjamin

If Franz Kafka’s friend Max Brod had honored his final wish to burn all his manuscripts and only this one letter had come down to posterity, Kafka would have survived as an author—even without Amerika (later retitled The Missing Person), even without The Trial and The Castle.

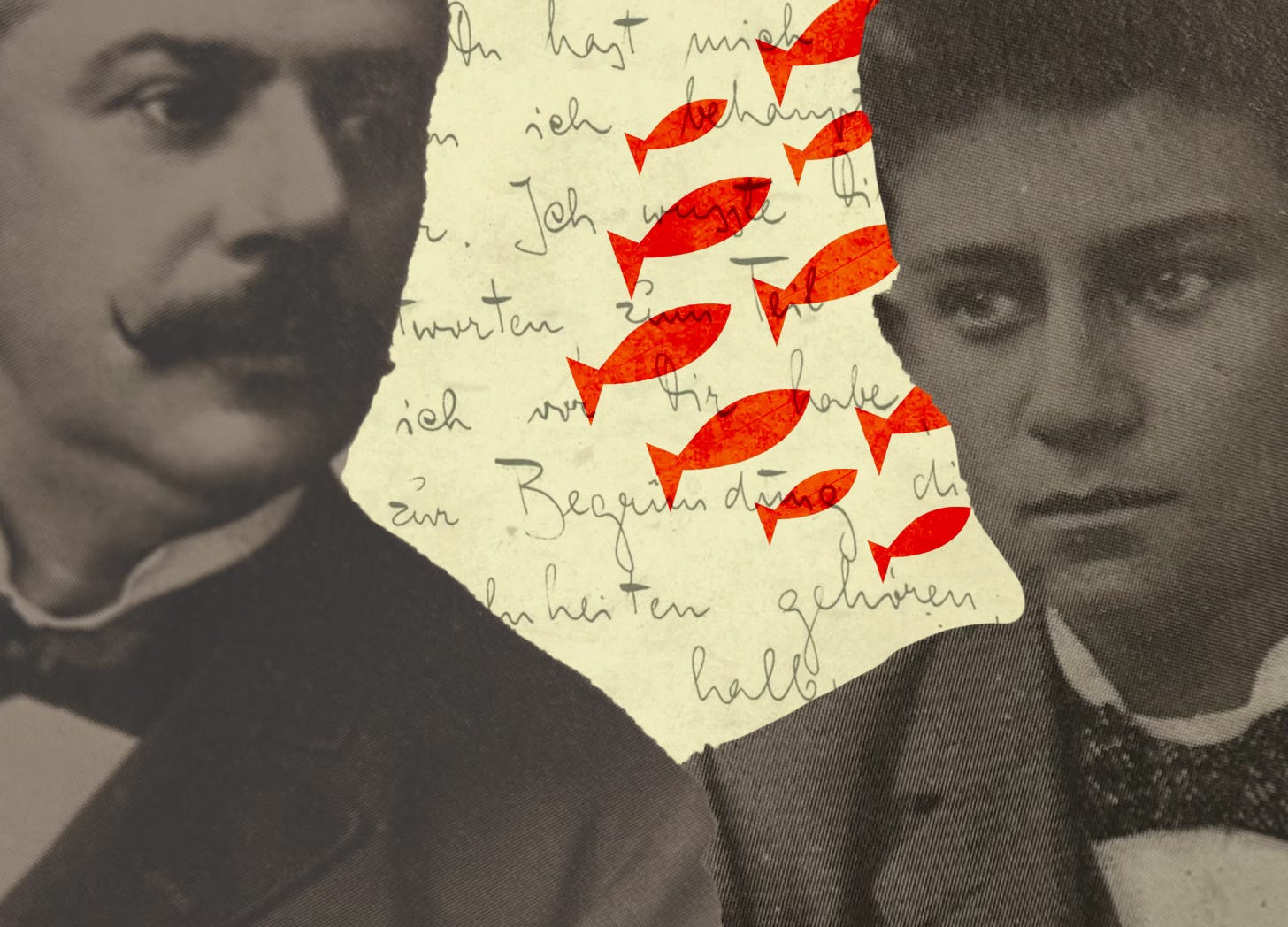

His Letter to his Father from 1919—one hundred handwritten pages—is a unique literary document. Its addressee, Hermann Kafka, never laid eyes on it; Franz never sent it or handed it over. He gave it to his lover Milena Jesenská, and it wasn’t published until 1952 in Die Neue Rundschau. Important Kafka interpreters such as Walter Benjamin were thus unaware of it.

This letter, which disguises itself as a self-accusation, is an immense reckoning conducted with all the lawyerly feints at Kafka’s disposal. For once, he wants to tell his father everything—the frightened son, consumed with shame and guilt, unfit for life and now terminally ill, not entirely unknown in the literary world but far from having even an inkling of his posthumous worldwide renown. For once, he summons all his strength and ladles bucket after bucket from the well of the past. And the past, as William Faulkner’s too-often-quoted line goes, is not dead; it’s not even past.

Some readers, including even Max Brod, have cast doubt on the veracity of the letter, or at least its biographical fairness. Was the father really such a monster? Weren’t there worse? But that is precisely what the letter is about: that neither of them was to blame. It was only the incompatibility of their two characters that had such a devastating effect on the son.

It is as if one person has to climb five low steps and another just one step, which, however, is as high as those five combined; the first will manage not only the five but also hundreds and thousands more, he will have led a great and very strenuous life, but none of the steps he has climbed will have had such significance for him as that one, first, high step for the second, a step impossible to ascend even with all his powers, one he cannot reach and naturally cannot get beyond either.

Others would have endured this father more easily; Franz leaves no doubt about that. But there can be just as little doubt that he is not simply making things up; after all, his father could have easily exposed such fabrications and thrown them back in his face.

All the quotes were genuine. His threats to “tear [Franz] apart like a fish.” The tyranny in his fancy goods shop, where he says of an errand boy, “Let him die, the sick dog!” About a relative who had served him faithfully until shortly before her death: “The dear departed has left me quite a mess.” None of this was invented by the son.

What vouches for the biographical truth are the details. Kafka remembers how as a small child, when he had whimpered too loudly for water, he was carried onto the balcony in his shirt in the middle of the night and locked out; how, changing in the bathing hut, he was always ashamed of being so scrawny and frail next to his robust and vigorous father, who tried in vain to teach him swimming strokes; how for years he trembled when attending temple “because you once mentioned in passing that I too could be called up to the Torah”; how his father reacted to the son’s happy moments with comments like “I’ve seen better,” or “I wish I had your troubles,” or “Some event!” or “What will that get you?” And finally, his table manners:

One wasn’t allowed to crunch bones, you were. One wasn’t allowed to slurp vinegar, you were. The most important rule was to cut the bread straight, but it didn’t matter that you did it with a knife dripping with gravy. One had to make sure no food scraps fell to the floor; under your place, in the end, there were always the most. At the table, one was allowed to occupy oneself only with eating, but you would clean and cut your nails, sharpen pencils, use a toothpick to clean your ears.

A hard-to-forget detail; like a toothpick, it bores itself into memory. No, the father was not exactly an agreeable man, was quick-tempered and stingy to boot, though jovial and well-liked outside the family. On rare occasions, he even let his son feel a trace of affection. Retelling the scene—when, out of consideration, the father remained at the threshold and only waved to his bed-ridden son—still brings Franz to tears: “At such times one lay down and wept for joy and weeps again now while writing it.” Just as he had whimpered for water as a child, this letter whimpers for belated love—or at least respect.

Kafka cannot rid himself of his father; his entire literature revolves around him. “My writing is about you, indeed I was only lamenting there what I could not lament at your breast.” At the breast of a man who, though merely a party to the case, perpetually cast himself as the judge in a trial waged against his son.

I had lost my self-confidence before you, trading it for a boundless sense of guilt. (Remembering that boundlessness, I once rightly wrote of someone: ‘He fears the shame will outlive him.’)

That someone is Josef K., the protagonist of The Trial, marked as autobiographical by more than just his name; Kafka freely paraphrases its concluding sentence here. The Letter to his Father can also be read as a veiled commentary on what is now his most famous novel. Everything, everything can be found here again:

But the hands of one of the gentlemen were at K.’s throat, while the other thrust the knife into his heart and turned it there twice. With failing eyes K. could still see the gentlemen leaning cheek to cheek close to his face to observe the moment of decision. “Like a dog,” he said, it was as if the shame should outlive him.

Yet the most enigmatic remark in this letter has rarely been given its due. Kafka writes of the long dark path he has traveled so far:

Until now I have deliberately left out relatively little in this letter, but now and later I will have to leave some things unsaid that are still too hard for me to admit (to you and myself). I say this so that if the overall picture should seem unclear in places, you do not think a lack of evidence is to blame, rather there is evidence that could make the picture unbearably stark.

Unbearably stark—what is he hinting at? Above all, what does he mean by “evidence”? Kafka scholarship remains silent on the matter. Did he fall in with pickpockets? Embezzle money from his office? Conspire with his sisters against the family? It cannot be the tangle of his repeatedly broken engagements—he speaks about those at length. Whatever it was, it must have been something fraught with taboo. Nor can he be referring to visits to brothels; after all, it was his father who once advised the shocked young Franz to go to one.

What one does not dare confess in letters—or even to oneself—one confesses under the cover of fiction; that, among other things, is what it’s for.

And so we turn to a passage from The Trial to which the word “stark” would certainly apply: the so-called flogger chapter. A risky leap, cushioned only by hypothesis. Whether Kafka had it in mind, we will never know.

What happens? One evening, Josef K. stumbles on a junk room in the building where he works. He hears a sigh coming from it. Seized by curiosity, he flings the door open. In candlelight he sees three men. What are they doing here? No answer. Without the candle, it would be a “dark room.”

One of the men, who evidently dominated the others and first drew one’s gaze, was clad in a sort of dark leather outfit that left his neck down to his chest and his entire arms bare.

Since when have employees of even the most enigmatic judicial authority worn leather? K. recognizes his two guards, Willem and Franz, who had informed him of his arrest at the beginning of the novel. The third man holds a rod in his hand. (A word not without a double meaning.) He is going to flog them because K. had complained about the guards to the examining magistrate.

K. feels guilty. This cruel consequence of his complaint had never been his intention, but despite an attempt at bribery, he cannot prevent what follows.

“Can the rod really cause such pain?” K. asked, examining the rod the flogger was swinging before him. “We’ll have to strip completely naked,” said Willem. “Ah, I see,” said K., looking more closely at the flogger, he was tanned like a sailor and had a wild fresh face.

A wild fresh-faced sailor, then. “Strip,” the flogger orders the guards. They unbuckle their belts. The flogger grips the rod with both hands and strikes the half-naked Franz.

Then the scream uttered by Franz rose, undivided and unchanging, it seemed not to come from a human being but from a tortured instrument, the whole corridor rang with it, the whole building must have heard it, “don’t scream,” cried K., unable to restrain himself, and as he looked intently in the direction from which the clerks must come, he bumped into Franz, not hard but hard enough for the dazed man to fall down and convulsively scour the floor with his hands; yet he could not escape the blows, the rod found him even on the ground; as he writhed beneath it, its tip swung up and down in a regular rhythm.

Here the sexual imagery practically leaps out at you. What else could this be but a homoerotic S&M fantasy that ruptures the novel’s frame? Regulars at Berghain would likely exchange knowing glances at this scene.

K. watches it not unlustfully, briefly considering stripping naked himself and offering himself to the flogger as a substitute for the guard. The next day, nearly in tears, K. orders his clerks:

“Clear out that junk room already!” he cried. “We’re drowning in filth.”

And that is the key word: filth (Schmutz). In the Letter to His Father, it heaps up in the passage where the father, in allusive terms, suggests that his son visit a brothel. The son speaks of his lust and his shame over it—and five times he speaks of the “filth” his father had burdened him with. A year later, in a letter to Milena, to whom he had given the letter to his father, he writes:

I am filthy, Milena, endlessly filthy, that’s why I make such a fuss about purity. No one sings as purely as those who are in the deepest hell; what we take for the song of the angels is their song.

No one ever sang more purely—that much is true.

This translation of Michael Maar’s essay “Engelsschmutz: Kafkas Process mit dem Vater” is an excerpt from his forthcoming book, Das violette Hündchen. Große Literatur im Detail, which will be published by Rowohlt in September 2025. It is published here with the kind permission of the author and Rowohlt Verlag.

English Translation Copyright © 2025 Ross Benjamin

Michael Maar is a literary scholar, writer, and critic. He first gained prominence with Geister und Kunst. Neuigkeiten aus dem Zauberberg (Spirits and Art: News from the Magic Mountain, 1995), for which he received the Johann Heinrich Merck Prize. In 2002 he was elected to the German Academy for Language and Literature, followed by the Bavarian Academy of Fine Arts in 2008. In 2010 he was awarded the Heinrich Mann Prize. His book Die Schlange im Wolfspelz. Das Geheimnis großer Literatur (The Snake in Wolf’s Clothing: The Secret of Great Literature, 2020) spent an extended period on Der Spiegel’s bestseller list. In 2023 a new edition of Leoparden im Tempel (Leopards in the Temple) was published. Michael Maar has two children and lives in Berlin.

Ross Benjamin is a translator of German-language literature and co-editor of FRANZ. He received a Guggenheim Fellowship for his translation of Franz Kafka’s Diaries, and he was awarded the Helen and Kurt Wolff Translator’s Prize for his rendering of Michael Maar’s Speak, Nabokov. His translation of Daniel Kehlmann’s Tyll was shortlisted for the 2020 International Booker Prize. His other translations include Friedrich Hölderlin’s Hyperion, Joseph Roth’s Job, and Daniel Kehlmann’s You Should Have Left and The Director.

Positively thrilling to read this. Thank you.

This is reminding me of the flogging section in Volume VI of Proust's In Search of Lost Time. Is the psychological implication that the son desires the father to punish him because it is a form of intimacy?